A Ticket to Hell – The Long, Lost Town of Walton Junction

Researched and Written by Randy D Pearson © 2019

From 1873 through the early 1920s, if you walked into any train station on the Grand Rapids & Indiana Railroad line and asked for a “ticket to Hell,” the agent would look at you straight-faced and hand you a one-way ticket to Walton Junction. Here is the short, fascinating history of that long, lost town.

Location, Location…

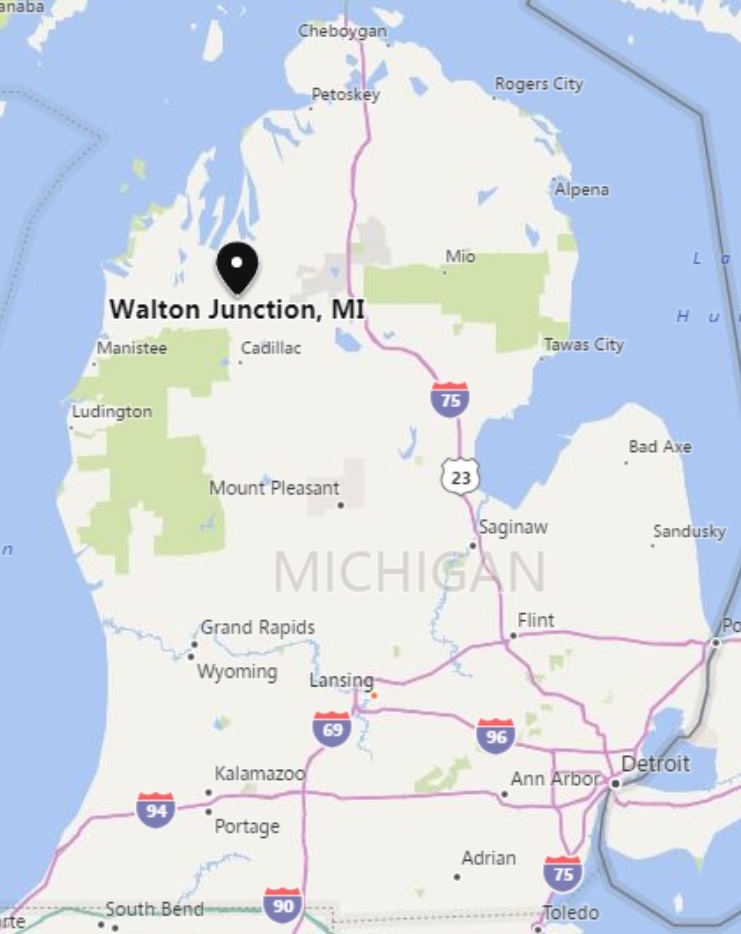

When I started writing my latest novel, Trac Brothers (the modern-day story of two brothers who inherit a nineteenth century handcar, put it on the train tracks, and have the adventure of a lifetime), I researched locations. I wanted this fictional action-adventure tale to take place in a real Michigan town. I started with Manton, a small city north of Cadillac on the west side of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula, because I have some dear friends who live there. From there I needed a place for the Rail Riders, the ‘friendly but weird’ group living off the grid, to reside. While scanning maps of the area, I found this intriguing location:

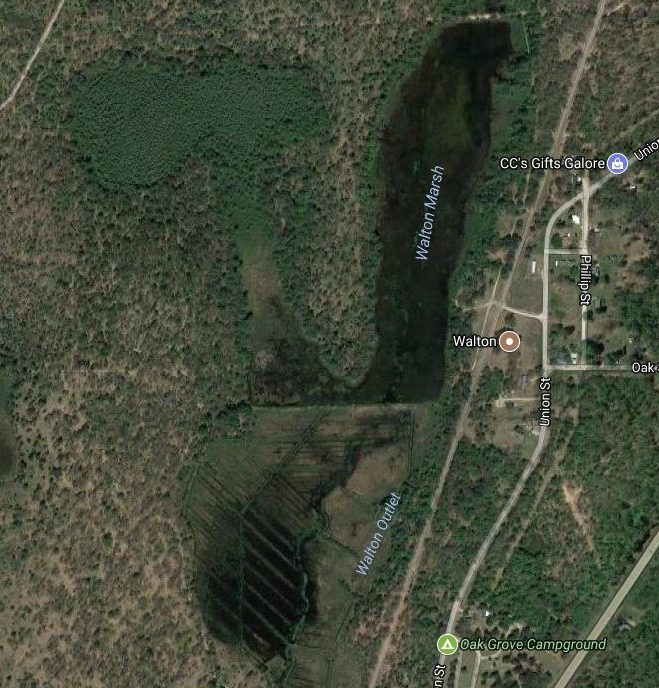

This 1-2 mile area, where three sets of train tracks meet in a rounding triangle, was the perfect place for my characters to live. While most maps either have this location unnamed or call it Fife Lake, the name Walton kept popping up. Walton Marsh, Walton Outlet, and then I found the original name for this area: Walton Junction.

An Internet search for Walton Junction brought up almost no information, so I went to Fife Lake, the nearest town a few miles to the north. The curator of the Fife Lake Historical Society, Craig Bridson, not only shed some light on this former town, but he even took me out to the location to see for myself what is left of Walton Junction. The short answer – very little.

Walton Junction, the beginning

The area north of Manton and south of Fife Lake had two things going for it – the lumber industry and the railroad industry.

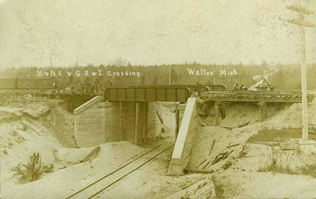

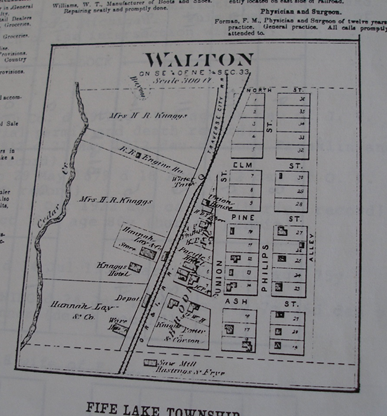

Most people agree that Walton Junction started in 1872, when the Stronach Lumber Company, a major timber harvester, opened a store and a boarding house. However, this village sprang to life in 1873 when a railroad depot was built at the junction of the Grand Rapids & Indiana (GR&I) and the Traverse City railroads. These tracks went off west toward Traverse City, south to Clam Lake (now called Cadillac), and north toward Fife Lake and Petoskey. There were originally a fourth set of tracks to the south of the triangle as well. Manistee & Northeastern (M&NE) ran under the other tracks just north of town, heading from Kaleva, north of Ludington, to Grayling. Those tracks have since been removed. The area where the tracks used to reside is still visible in the above satellite picture. (The picture below is showing the now-removed tracks travelling under the still-existing tracks.)

With this being the starting point of their branch line to Traverse City, GR&I selected this area as the location for their construction headquarters.

Walton Junction’s Founding Three

This new village prospered due in part to three enterprising men – AF Phillips, HA Ferris, and Robert Knaggs.

A foreman on the GR&I construction crew, Abram F Phillips built the first house in early 1873. From there he began to keep boarders. Within a few years, he started one of Walton Junction’s hotels.

Henry A Ferris, a land looker, opened a road from Traverse City to the Manistee River by way of Walton.

With both the promising location as a railroad junction and a road to the river, Walton Junction was officially founded in 1873.

Robert Knaggs, while moving to Traverse City in 1867, was robbed on his way out of Detroit. Left with only 18 cents, he found a job as a carpenter at Hannah, Lay & Co. He worked there for eight years before he moved to Walton Junction and opened the first hotel, the Walton Inn, in 1875.

By 1877, two smaller hotels popped up (the GR&I House, owned by Phillips, and the Commercial Hotel), as did The Stronach Lumber company and store, and a train ticket booth. By now, the population had grown to around 100.

With travelers changing trains and experiencing layovers, the hotels prospered. 1880 saw the first saloon, built by Ferris. This watering hole had many different types of customers. The railroad workers and the travelers stopped in for drinks, as did the many lumberjacks and the rivermen in the area. These rivermen, sometimes called riverhogs or just hogs, moved the lumber down the Manistee River. The location of Walton, between the Manistee and Boardman Rivers, made it handy for hundreds of men to get together, for some drink and a friendly fight on weekends.

Saloons, Hotels, and Bawdy Houses

By 1885, in addition to the three hotels, (Knaggs’s Walton Inn, which had become the Exchange, the GR&I, and the Commercial), there were now as many as ten saloons. The village also had two general stores, a blacksmith, a druggist, a carpenter, a station agent, and two doctors (who were undoubtedly kept busy due to all the brawls – but more on that later). Also, if the rumors are to be believed, there were upwards of four bordellos, referred to as “Bawdy Houses.”

One entrepreneur, Dennis Thralls, ran a furniture store, was the undertaker, the justice of the peace, and the postmaster.

The regular population was now up to 200, but because this was the only place between Traverse City and Cadillac where a tired and thirsty laborer or traveler could get a drink and feminine companionship, Walton Junction could swell to upwards of 2,000 on the weekends. On Fridays, around suppertime, trains from the north and south would let the young men loose on the town. The respectable women ushered their children and husbands into the security of their homes, staying inside behind locked doors until Sunday evening.

Them’s Fightin’ Words!

After an evening of hard drinking, the fighting would soon commence. Stories of the brawls between the lumberjacks (often called Jacks) and the hogs were legendary, as was the brutal rivalry between the Jacks and the railroad men. The railroad crews from Clam Lake would head to Walton Junction, looking to mix it up with the Jacks coming over from Traverse City. Sometimes, even the best of friends just wanted to let off some steam.

Given that the visitors were primarily young and single men, as the evening wore on, drunken brawls were common. In fact, they seem to be the major source of entertainment. These fights did not involve weapons such as guns or knives. The men would simply stand toe to toe and slug it out. If a man was knocked down, he was given room to get back on his feet.

Lumberjack Smallpox

The most dangerous fights involved the Jacks. When one of the contestants could no longer stand, it was considered acceptable for the victorious lumberjack to “brand” the loser by stomping on his body with the his steel caulked boots. They called this pocked-marked pattern, “lumberjack smallpox.” The bleary-eyed losers would often limp back into their camps on Sunday night having lost a tooth or two (and in one case, a man showed up with his ear in a paper sack, looking for a doctor to sew it back on) but having gained a man-made case of smallpox.

Walton became notorious for hundreds of miles, hence the “ticket to Hell” moniker. Without much in the way of law enforcement (they had no sheriff or constable, and though they were between Grand Traverse and Wexford Counties, they did not receive help from either), it was mostly left up to the bouncers and bartenders to keep the peace.

Cranberry Time

Around 1890, DeWitt Clinton Leach, the Grand Traverse Herald publisher, established a cranberry farm, Walton Junction’s only actual industry.

A few blocks south of town sat a creek. Leach had a 200-foot earthen dam built through the creek, producing a marsh to the north. This created the perfect area to the south of the dam to grow the cranberries. He added sluice gates to control the water levels, and had trenches dug, planting the cranberry bushes on the ridges in the bog.

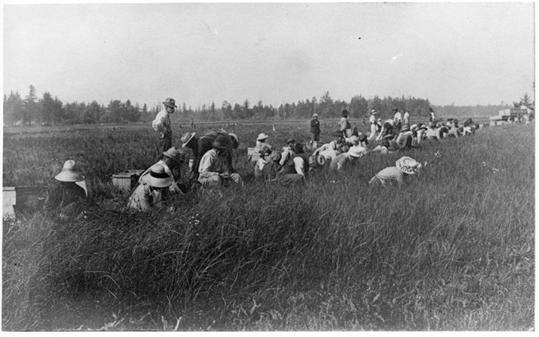

The first several years were immensely successful, with annual yields of around 1,000 bushels, harvested mostly by Native American pickers. However, Mother Nature had other plans. On July 10, 1898, the region experienced a hard freeze, destroying the entire cranberry crop that year.

He had even worse problems with the muskrats, who tunneled through the dam and dug in the ridges, toppling the bushes. Nothing Leach tried worked, and by around 1910, he sold the failing business to GA Babcock, who then closed it entirely around the early 1920s.

The earthen dam still exists today, separating the Marsh from the Outlet. The occasional cranberry bush can be seen scattered throughout the bog.

The Peak and Decline

Walton Junction’s regular population (not counting those wild weekends) peaked in 1903 at around 250 people. By then, the timber was gone, so the lumberjacks moved on. The automobile business was starting to pick up, so people weren’t using trains for daily travel as much anymore. This caused some of the businesses to relocate. At this point, only the Exchange Hotel remained, as did a couple of restaurants, a general store, carpenter, and one of the saloons.

By 1917, the population was back down to 100. Then the train station closed around the time that the newly built highway bypassed the town, signing Walton Junction’s death warrant.

With businesses closing, the people began to move away as well. With no one to sell to, the property owners would just abandon their houses. The ownership reverted to the county. A few studious entrepreneurs waited until auction time, buying up the properties for cheap. They weren’t doing it for a possible Walton Junction revival, though. Instead, they would gut the houses for everything valuable, including the lumber, selling it all off. Then they would stop paying the taxes, and again let the land revert to the government. That is the main reason why Walton Junction can’t be called a ghost town. There is simply nothing left. Even most of the foundations have been hidden by the years.

The only sign that Walton Junction ever existed is, quite literally, a sign.

Reclaimed by Nature

The Walton Junction Cemetery, like the rest of the town, has been reclaimed by nature. There are no tombstones or obvious areas where the people were laid to rest. It looks more like a forest than a cemetery.

In fact, most of the bodies had long ago been relocated about a mile away to the new Walton Cemetery, on Medrak Lane in Fife Lake. However, rumor has it that as many as thirteen bodies or parts of bodies remain here (workers, landowners, Native Americans, or transients), spread out among the trees. This is still a sacred place, but with people who are lost to time.

Below is a picture of the cemetery. Note the piece of wood fragment affixed to two metal poles. This much older cemetery sign still bears some faded words, but time has mostly erased them.

Walton Junction had a rapid rise and an equally fast decline, but was a hell of a good time when it was around.

Bibliography

The Traverse Region, Historical and Descriptive, with Illustrations of Scenery and Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers – HR Page and Co – 1884 Chicago

Walton Junction, a Town with a Colorful History – Record-Eagle – Traverse City, MI

Vinegar Pie and Other Tales of the Grand Traverse Region – Al Barnes – Wayne State University Press, 1959, 1971, 1984, Literary Licensing, LLC, Jul 1, 2012

History of the Grand Traverse Region – Morgan Lewis Leach – Central Michigan University by the University Press – 1883

Early Walton was a Hell of a Place – Larry Wakefield – Summer Magazine – Traverse City Record-Eagle – May 24, 1991

Historical photos and documentation courtesy of the Fife Lake Historical Society – Craig Bridson, Curator

Modern photos © 2018 Randy D Pearson